A couple of people at events I've done recently have asked me about the titles of the books; where they come from, and which comes first, the title or the story? To which my answer is usually, "Errrrr....", because of course there is no hard-and-fast rule about it - at least, not the way I work. But here's a quick list of titles and how they came to be, in case anyone else is interested.

The title of Mortal Engines didn't arrive until long after the book was finished. One of the first things I thought of when I started the story was a title; Urbivore!, which I thought was pretty neat. Scholastic, however, didn't, so they asked me to change it prior to publication. I tried out out a lot of other names which didn't work, until I was reduced to going through the Dictionary of Quotations looking for anything that related to cities, engineers, engines... The one I eventually settled on is from Othello: "And, O you mortal engines, whose rude throats/The immortal Jove's dread clamours counterfeit,". It's strange now to think that it was ever called anything else.

Predator's Gold, on the other hand, was easy peasy; the phrase cropped up early on in the manuscript, and instantly looked like a title. Infernal Devices was trickier. I started out writing a huge book that was meant to conclude the trilogy. I planned to call it A Darkling Plain, which is a quote from Matthew Arnold's Dover Beach, a bleak and beautiful poem about the importance of love in a world where religious faith has proved unsustainable 'And we are here as on a darkling plain/Swept with confus'd alarms of struggle and flight/ Where ignorant armies clash by night.' I think I was drawn to it at first because it sounded cool, and suited the world of the books, what with its darkling plain and ignorant armies and all (I think I'd considered it as a title for Mortal Engines). But the elegiac tone of it appealed too, and felt more and right as I began to realise where the story of Tom and Hester was going. Unfortunately the book ended up much too huge, and kept breaking in half, so I decided to split it into two volumes. I wanted to use a phrase from TS Eliot, 'Look to Windward' as a title for the first installment, but Ian M Banks had written with a book of that name, so I changed mine to Infernal Devices; in retrospect my least favourite title in the quartet.*

With A Darkling Plain wrapped up, I left the World of Mortal Engines behind and set to work on finishing my King Arthur book, which was known for many years as My King Arthur Book. It was one of my editors at Scholastic, the excellent Katy Moran, who eventually suggested Here Lies Arthur, a neat double meaning and a reference to Malory into the bargain. And it was while I was working on that that I thought of the name Fever Crumb, and decided I'd have to go back to the WoME, find out who she was, and write a novel about her; a novel whose title would be the main character's name, in the tradition of Jane Eyre and David Copperfield (for a while I even called it The Life and Adventures of Fever Crumb).

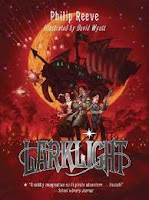

Meanwhile, Larklight was a name that I'd had kicking around for decades, ever since it came to me in a dream (it might have been suggested by Fairlight, a place in East Sussex). Starcross is a railway station which I pass on the way to Exeter (and was coincidentally one of the stops on Isambard Kingdom Brunel's atmospheric railway), while a Mothstorm was what faced us when we moved into our present house - the previous owner had stored un-cured wool in the cupboards. And No Such Thing As Dragons was another book with no name for a long while, until in desperation I thought, What would Geraldine McCaughrean call it?

A Web of Air is based on another quotation, this time from Charlotte Bronte - 'We wove a web in childhood/ A web of summer air' - which seemed to sum up both the conquest-of-the-air theme of the story and the lighter, slighter, sunnier tone that I was aiming for. And the new book has proved another tough one: for a long time it was just called Fever 3 while I dithered about with long lists of possible titles, some rejected by Scholastic because 'They don't have child appeal**', others which seemed like a good idea for a time but then lost their relevance as the story developed. (For a few months it was called Nomad's Land, but that came to seem too light and punning for what turned out to be quite a tragic and bloody tale). In the end I found the title lurking in the text itself; Scrivener's Moon; the season in which the action takes place, and a hint that Fever will be discovering more about her Scriven heritage...

* There's no copyright on titles, but it seems to me to be a good idea to try to avoid using one that someone else has used, especially if their book is recent or well known. Since writing Infernal Devices I've found that there's a book of that title by KW Jeter, which is annoying. And to add to the possible confusion, Cassandra Clare has published a series called The Infernal Devices (and by some peculiar coincidence she has another called The Mortal Instruments). Nowadays, of course, the first thing I do upon thinking of a title is to google it and see if it's already taken, but I had no access to the internet while I was writing the Mortal Engines quartet - if I had, it wouldn't be called the Mortal Engines quartet, since a quick visit to Amazon would have told me that there were already two other books with that title: one a collection of stories by Stanislaw Lem and the other a book on sports medicine.

**This is also the reason why my World Book day story Traction City Blues has had its title changed to plain ol' Traction City.